In September 2025, I took part in a sea expedition across the Barents Sea to the Franz Josef Land archipelago and further south, along the island of Novaya Zemlya.

…The journey began from the port of Murmansk through the Kola Bay, from where, accompanied by a pilot boat, we continued north into the open, cold waters of the Barents Sea. We had to cover more than 700 nautical miles, which subsequently required three and a half days of non-stop sailing to reach the first islands of the archipelago.

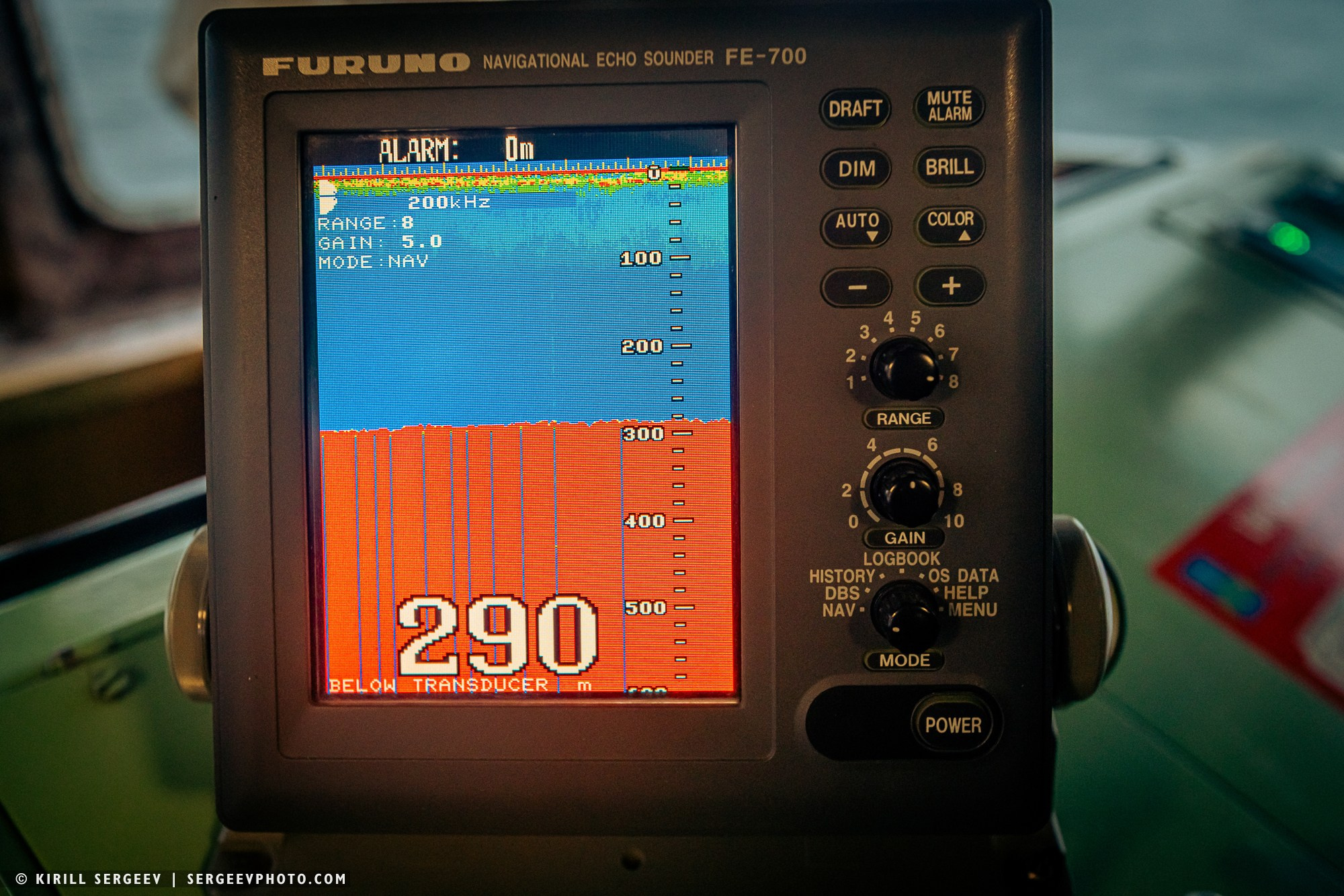

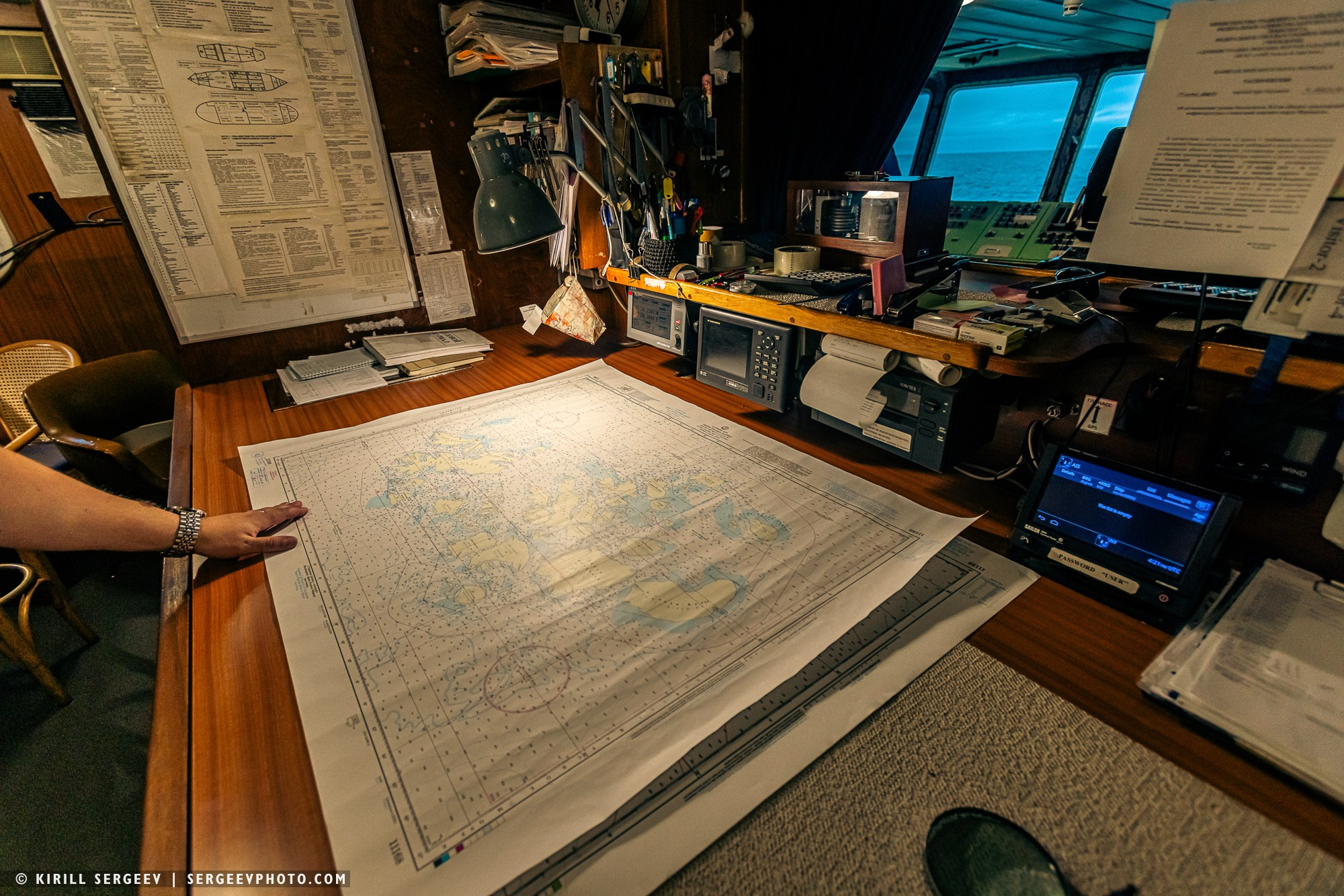

Our home for the entire voyage was the research vessel Professor Molchanov. This is a Russian ice-class vessel, built in 1983 in Finland for oceanographic and polar research in the Arctic. Named after meteorologist Pavel Molchanov, the vessel is 71 meters long, displaces approximately 2,140 tons, and is capable of autonomous navigation for up to 70 days. We travelers were allowed to climb onto the captain’s bridge and admire the instruments, controls, and the crew at work. As a former pilot and an expert in aircraft control, I was interested in learning how to operate a surface vessel.

The Barents Sea is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean, located north of Norway and Russia, between the coast of the Kola Peninsula and the Svalbard, Franz Josef Land, and Novaya Zemlya archipelagos. Weather permitting, coupled with the high intensity of charged particles emitted by the Sun, the beautiful flashes of the aurora borealis can be seen in the autumn night sky above the sea. The Barents Sea’s fauna is incredibly rich and diverse, thanks to its unique location at the junction of the warm Atlantic and cold Arctic waters. Majestic whales, such as the bowhead, humpback, and minke whale, as well as dolphins, including white-beaked whales and killer whales, inhabit the sea. Millions of seabirds, nesting in famous bird colonies, reign over the vast expanses of the sea: puffins, guillemots, kittiwakes, and northern fulmars, creating a deafening and unforgettable hubbub.

Hayes Island. Our first long-awaited stop and landing on land after several days of living at sea. The island was discovered in 1901 by the Baldwin-Ziegler expedition and named in honor of the American Arctic explorer Isaac Hayes. Since the summer of 1957, Hayes Island has become the main scientific base of the archipelago. Initially, the Druzhnaya observatory was opened here, later renamed in honor of the legendary polar explorer and radio operator Ernst Krenkel. This is the northernmost meteorological post in Russia. Today, the station is relegated to the status of a reference station, and its staff is small — just a few people conducting meteorological observations of the atmosphere, the Earth’s magnetic field, cosmic rays, the northern lights, and permafrost. Another unique site that has already become history is the world’s northernmost post office, Arkhangelsk 163 100. It opened in 2005 and operated on a completely unique schedule—just one hour a week, on Wednesdays. The post office is currently closed. One of the island’s most striking and tragic sights is the Ilyushin Il-14 aircraft. Its story came to a tragic end on February 12, 1981. The plane was flying from Moscow, delivering scientists and equipment to the observatory. While landing in the polar twilight, the crew lost sight of the runway lights. Now it rests in its eternal parking lot, serving as a silent reminder of the tragedy and the courage of those who work in the harsh Arctic conditions.

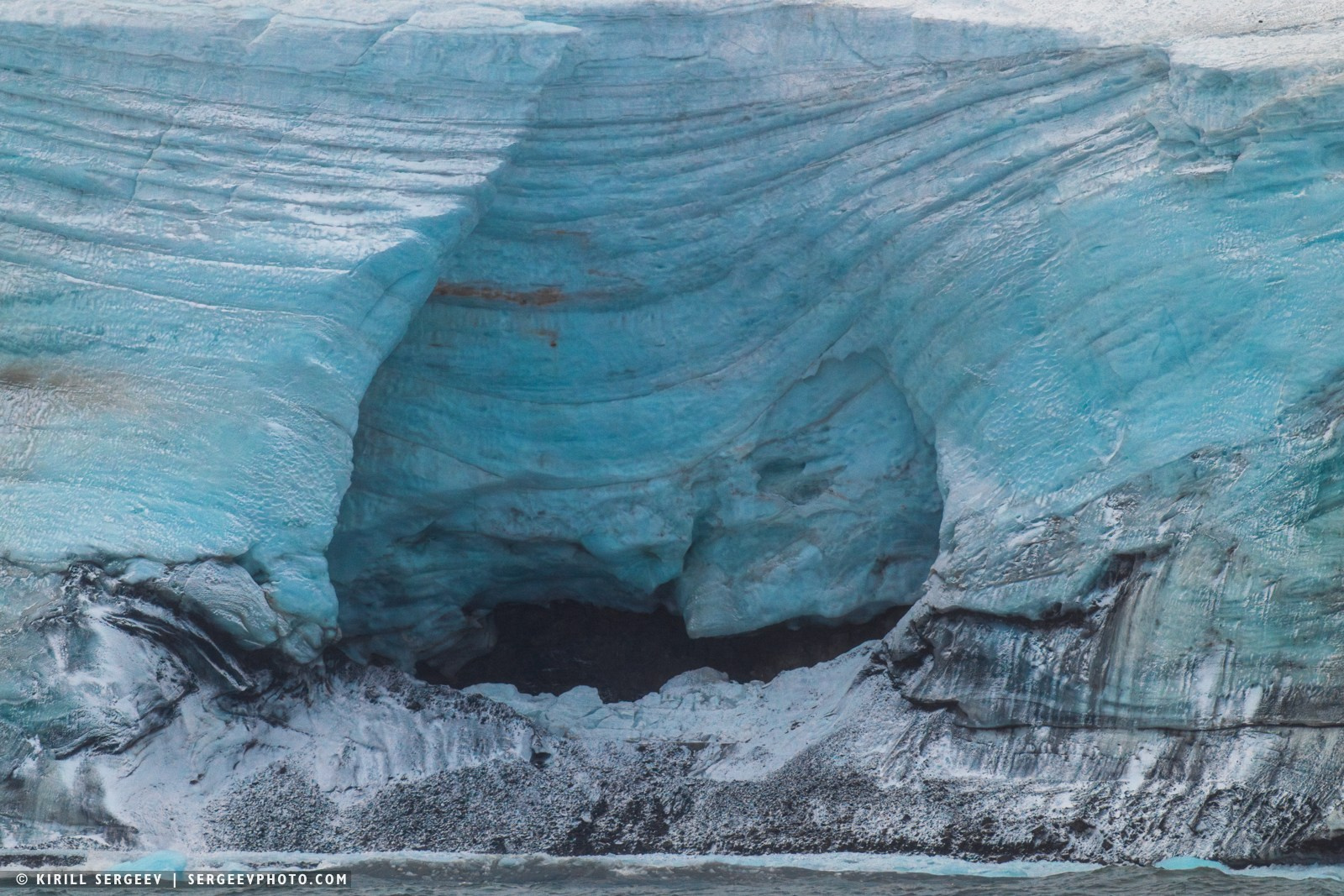

Next we went to Champ Island. This is one of the most mysterious and visually stunning places in the entire Arctic. This small patch of land, lost in the icy expanses, became widely known thanks to a unique phenomenon — countless stone balls, as if scattered along its coast by a giant invisible hand. These balls are concretions, not spherulites (the latter are formed from crystals). The mechanism of their formation is similar to the birth of a pearl in a shell. In the northwest of the island is Cape Trieste, which also bears traces of history. In August 2006, it was here that a fragment of a ski was discovered, the age of which is estimated at more than a hundred years. Champ is a typical Arctic landscape: rocky plateaus, steep slopes and glaciers. Thus, the tongue of the glacier descending to the sea forms a steep front. The glacier continuously interacts with its environment: it produces icebergs and shapes the cold microclimate of the coast.

Hooker Island. Tikhaya Bay. The island covers an area of 508 square kilometers, and almost all of its territory, with the exception of a few coastal areas, is covered in ice. It is on its western coast, in Tikhaya Bay, located on Cape Sedov, that there is a place that is rightfully considered the informal “capital” of the archipelago and its main historical gateway. This is the former polar station “Tikhaya Bay” — the first Soviet outpost on Franz Josef Land, founded in 1929 and becoming a symbol of the scientific exploration of the Arctic. For three decades, the station was the main scientific and administrative base on Franz Josef Land, where comprehensive research was carried out in the fields of meteorology, aerology, glaciology, geophysics and biology. The station was finally closed in 1960, when observations were transferred to the Krenkel Observatory on Heiss Island. Today, the former station site is an open-air museum complex and a seasonal base for the Russian Arctic National Park.

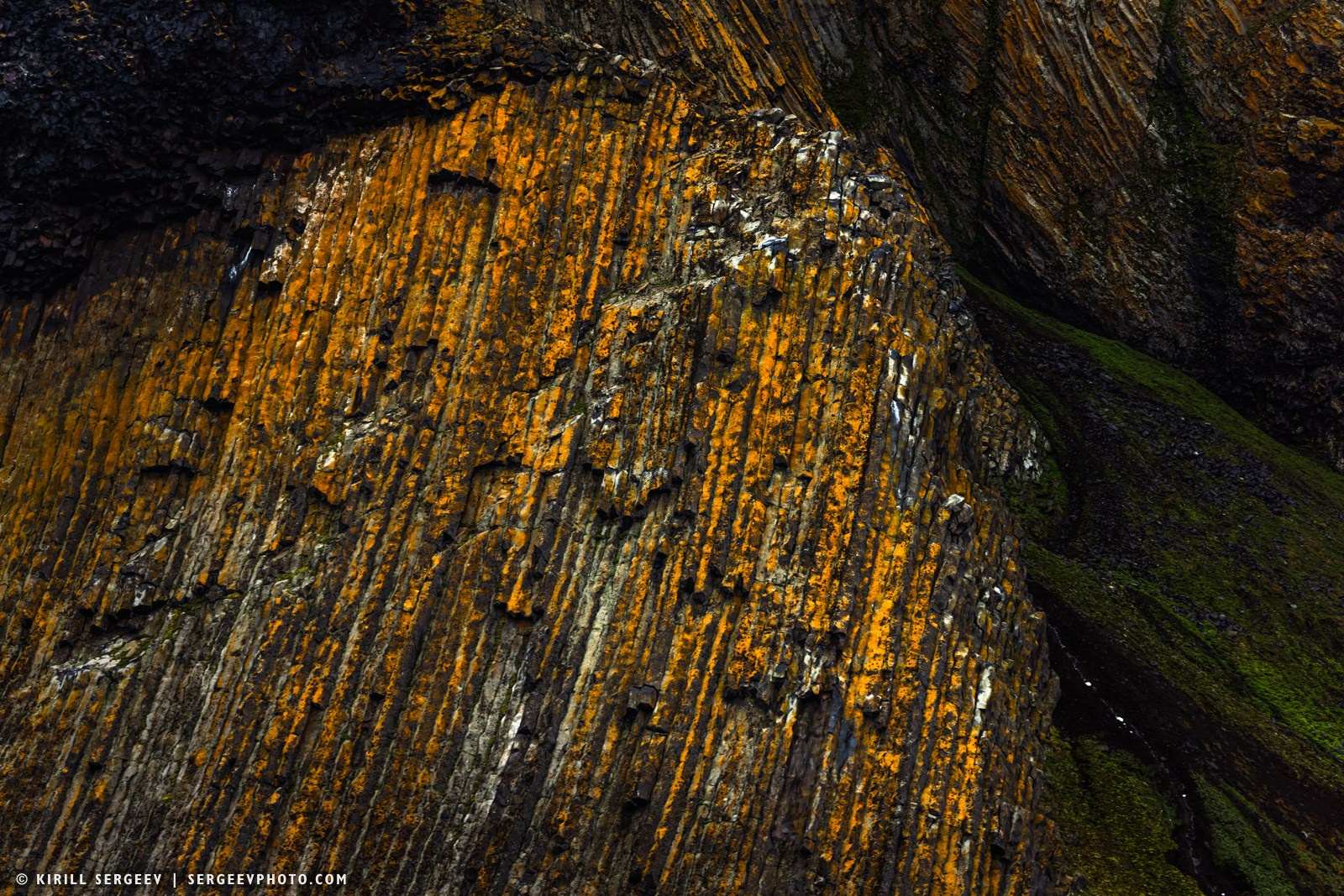

An integral part of the Tikhaya Bay landscape is the majestic Rubini Rock, a colossal basalt cliff approximately 174 meters high, named in 1895 in honor of the Italian opera singer. This name proved prophetic: today, the rock is one of the largest and noisiest bird colonies in the entire archipelago. Its slopes are composed of geometrically perfect hexagonal basalt columns formed during the solidification of lava 100-150 million years ago. These natural “columns” create ideal nesting conditions.

An integral part of the Tikhaya Bay landscape is the majestic Rubini Rock, a colossal basalt cliff approximately 174 meters high, named in 1895 in honor of the Italian opera singer. This name proved prophetic: today, the rock is one of the largest and noisiest bird colonies in the entire archipelago. Its slopes are composed of geometrically perfect hexagonal basalt columns formed during the solidification of lava 100-150 million years ago. These natural “columns” create ideal nesting conditions.

Unfortunately, due to the strong swell and the impossibility of approaching the shore, much less landing on it, we weighed anchor and sailed west along Rudolf for some time, but a decision was made, as a bonus, to overcome the 82nd parallel! We went north to reach this mark. 82° north latitude, according to the captain, is not crossed by any ship except the icebreaker fleet for many decades. We noted this, took a photo at the very edge of the geographic maps of the Earth and turned back. To go through the entire archipelago to the very south…

Northbrook. This island, one of the southernmost in the archipelago, was long considered a single geographical entity. However, in 1985, it was discovered that a melting glacier had opened a channel, dividing it into two parts—West Northbrook and East Northbrook.

East Northbrook is an uninhabited island in the southern part of Russia’s Franz Josef Land archipelago. It covers an area of 254 square kilometers, with its highest point reaching 344 meters above sea level. The island is considered one of the most accessible in the archipelago and, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, frequently served as a base for various polar expeditions.

West Northbrook Island is a small uninhabited island in the southwestern part of Franz Josef Land. It is the youngest island in the archipelago, having formed after the breakup of the single island of Northbrook. Cape Flora, located at the southern end of West Northbrook Island, is a raised rocky plateau with steep shores. Above it, cliffs rise up to 303 meters high. Geologically, the cape is composed of rock. The cape lives up to its “botanical” name, being one of the greenest places in the entire archipelago. Its territory is covered with moss, and in the summer months, brightly colored arctic poppies can be found on the higher ground. This relatively lush vegetation actively develops under large bird colonies located on the basalt cliffs of the cape. The abundance of life attracts top predators to the cape — polar bears and arctic foxes, for whom the bird colonies become a source of food.

Having traveled about 20 km from Cape Flora further to the southwestern part of the archipelago, we reached Bell Island. Our ship dropped anchor at its northern end. The small Bell Island, the area of which is only 10 square kilometers, was discovered in 1880 during the first expedition of the English explorer Benjamin Leigh Smith. The island has a characteristic horseshoe shape, turned to the west. The calling card of the island, which determined its name, was a mountain on the southeastern coast. Its outlines resemble a giant bell (which prompted Leigh Smith to give it the appropriate name (English Bell — “bell”). The height of this natural formation reaches 343 meters, while the main part of the island is represented by a lowland plain. Nielsen Bay cuts deeply into the central part of the land.

The island’s, and perhaps the entire archipelago’s, main historical landmark is a modest wooden house known as Eira’s House. It’s not just the oldest structure on Franz Josef Land, but a unique artifact from the heroic era of polar exploration that has survived to this day. The house was built in July 1881 by members of the British expedition led by Benjamin Lee Smith on the steam-sailing yacht Eira.

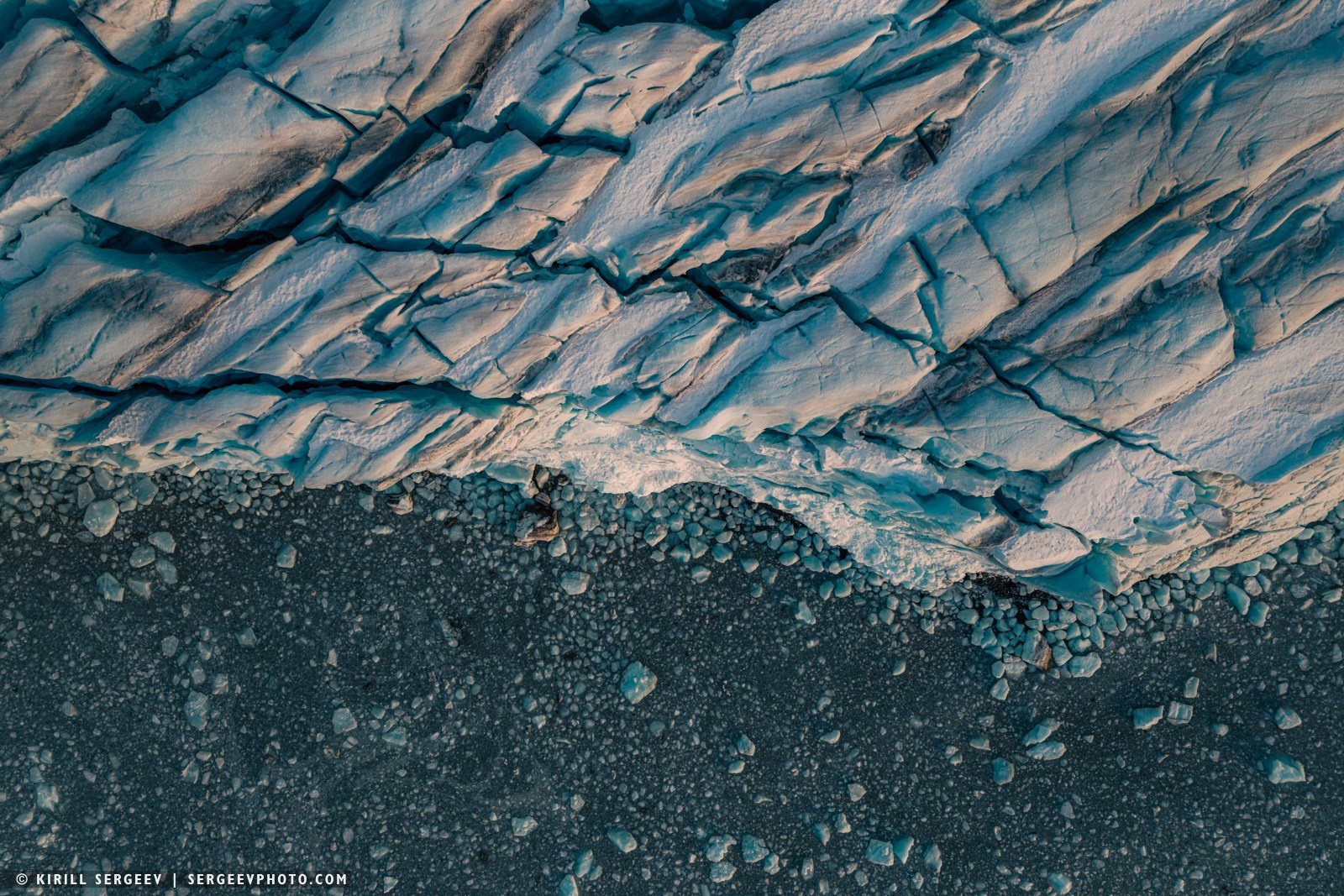

Less than a kilometre east of Bell Island, across the narrow Eyre Strait, lies the larger Maybelle Island, named by Lee Smith after his niece. It covers about 40 square kilometres and is 9.5 kilometres long. The island’s terrain is noticeably higher, with the highest point of the ice cap reaching 356 metres above sea level. We didn’t venture up to it by boat, but I took my drone from Bell Island and flew across the strait to get a good look at Maybelle’s glaciers and cliffs from above.

When visiting Franz Josef Land, you can’t miss Cape Tegetthoff, located at the southern tip of Hall Island. This fascinating geological feature of the archipelago is washed by the cold waters of the Barents Sea to the south and sheltered by Surovaya Bay to the north. Immediately beyond the cape begin the Zavaritsky Cliffs—a 15-kilometer-long mountain range with heights of up to 500 meters. The cape’s most notable formations are two approximately 25-meter-high outliers composed of basalt that have undergone intense erosion. These cliffs, also known as the “Tegetthoff Gate, ” form a natural architectural complex framing the entrance to Surovaya Bay and are a distinctive feature of the cape.

Our last stop on the archipelago is a small island located in the southeast of Franz Josef Land. Wilczek Island. This small piece of land, just over 50 square kilometers in area, has forever entered the annals of the discovery of the Arctic. It was its rocky shore that became the first point of the archipelago where human feet set foot on November 1, 1873 — members of the Austro-Hungarian expedition under the command of Julius Payer and Karl Weyprecht. The relief of Wilczek Island is determined by two glacial domes: the northwestern one is 187 meters high and the southeastern one is 122 meters high, connected by a glacial bridge. The highest point of ice-free land — 42 meters — is located in the far west near Cape Schilling. A distinctive geological feature of Wilczek Island are its massive basalt stocks — vertical intrusive bodies that formed in the sedimentary rock during the archipelago’s period of active volcanic activity…

So, in one week, we’ve sailed through several islands of the Franz Josef Land archipelago and are saying goodbye. Our “Professor Molchanov” is heading south beyond territorial waters, toward Novaya Zemlya Island.

Novaya Zemlya emerged from a haze of fog and snow flurries, illuminated by a golden sun, approximately 19 hours after leaving the Franz Josef Land archipelago. The weather was unfriendly, a good wind blew, and strong waves crashed against the stern. After some time, we approached the Bolshie Oranskiye Islands and circled around them for a while. In the shallows of the largest island, I was able to see a fairly large walrus rookery through a telephoto lens. Unfortunately, we were unable to get close to it, and due to strong gusty winds, launching the copter seemed too risky. We had to photograph them to the limit of our capabilities through a 600mm lens and a 1.4x converter. We sailed along the northern tip of Novaya Zemlya, passed Mys Zhelaniya, turned southeast along the coastline, leaving behind the polar station of the same name, Mys Zhelaniya, which operated from 1931 to 1997. We entered the Pechora Sea…

On the eastern side of Novaya Zemlya, the sea was much calmer, there were no such winds, the sky cleared, the waves more or less died down and we were able to stop and drop anchor in the Ice Harbor near Cape Sporyy Navolok. Novaya Zemlya sheltered us from the cyclone approaching from the west. From the stern of the ship on the cape, we were able to see several polar bears. In the autumn, a high concentration of these predators is observed in the north of the island, waiting for the ice to form. Here, they are the rightful masters! To ensure a good view of them, several boats were launched — Zodiacs and crew took tourists to the shore, where the white predators feel at ease and ate kelp washed up on the shore. Afterwards we weighed anchor and sailed south across the Pechora Sea, towards the growing polar lights…

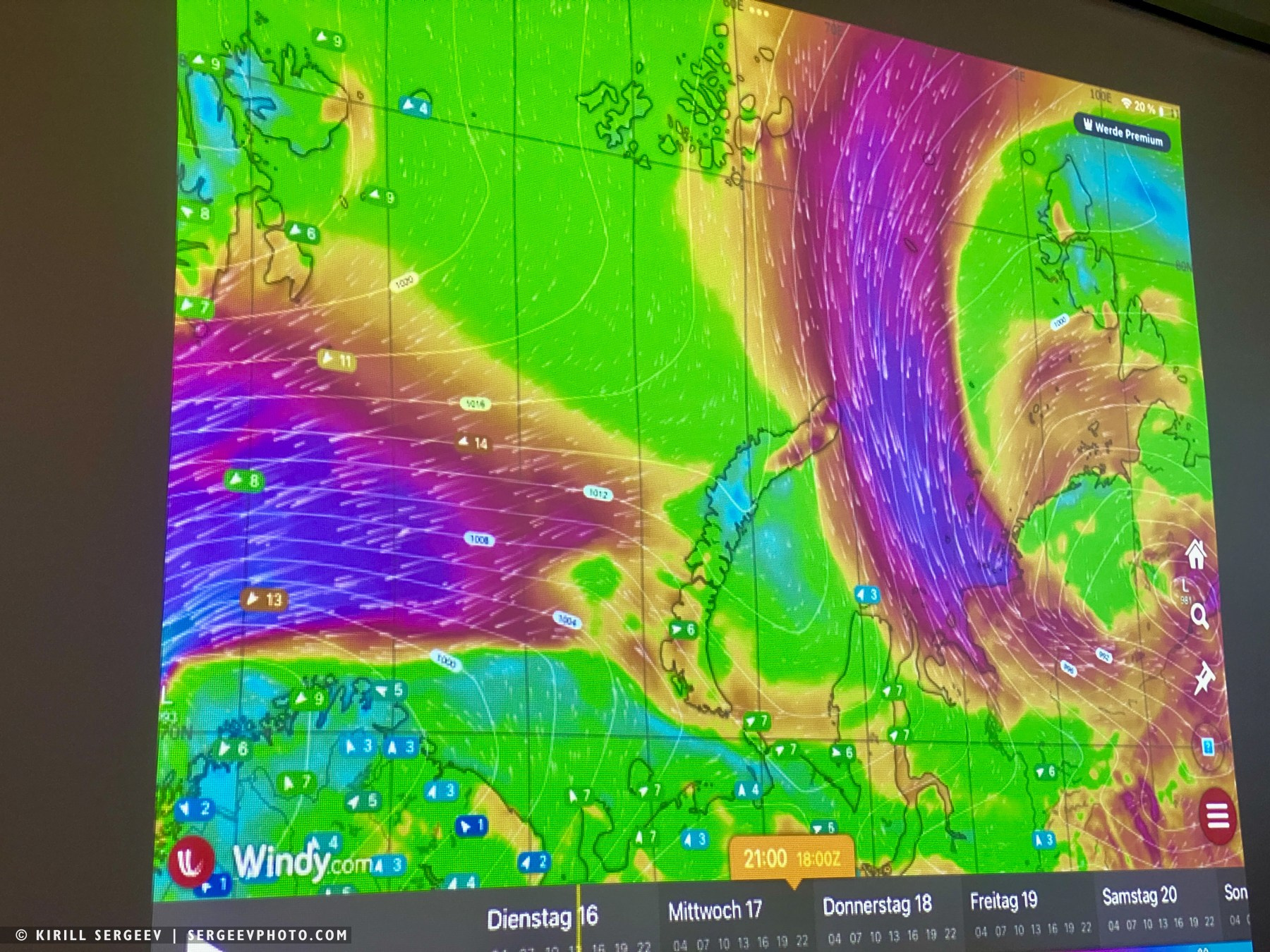

We spent three days sailing along the Pechora Sea alongside Novaya Zemlya. On the other side of the archipelago, in the Barents Sea, a powerful cyclone was raging, which is why we chose to sail along the eastern side rather than the western. But we also had to hurry, as bad weather was also descending from the north, and we were racing south at full speed toward the Kara Gates. Nevertheless, the bad weather caught up with us a bit, and the sea became stormy, reaching a 7-level surface swell.

The Kara Gates were closed. That day, there was a siphoning sound from the west like in a wind tunnel. We went even lower, past Vaygach Island to the mainland and dived into a strait with an interesting name, Yugorsky Shar (The strait’s name has a mixed origin and consists of two parts: “Yugorsky” comes from the historical name of the region, Yugra (also known as Yugoria); “Shar” is a term borrowed by the Pomors (Russian settlers of the White Sea region) from the Finno-Ugric languages, where it means “sea strait”). This is a narrow strait about 40 kilometers long, separating the Yugorsky Peninsula of mainland Eurasia and Vaygach Island and connecting the Barents and Kara Seas. Its width ranges from 2.5 to 16 kilometers. The strait has a long history of navigation: the Pomors have used it since the 11th century, and in the 16th century it became part of an important trade route, the Great Mangazeya Passage. Currently, the Yugorsky Shar is part of the Northern Sea Route, serving as an alternative and safer route for ships during unfavorable conditions in the main Kara Gate strait. On the shores of the strait, we observed such traces of human civilization as wooden lighthouses, the ancient Pomor village of Khabarovo, converted into a forced labor camp in 1934, the polar station “Bely Nose”, and also in the distance the small village of Varnek, located in the south of Vaygach Island in Varnek Bay. In the strait, I continuously photographed flocks and wedges of geese and seagulls. Life here was unusually in full swing.

Having left the Yugorsky Shar behind, we entered the Pechora Sea and set course for Murmansk. The journey was not short; we still had about 600 nautical miles (approximately 1,100 km) to cover to the port. The landscape and weather changed slowly. Sometimes the sun would shine, sometimes the sea would be shrouded in thick fog. The ship made a couple of stops at the Koninskaya Bank, where the crew and some travelers cast their spinning rods, then hauled seafood onto the deck to the incessant hubbub of seagulls. For the first time in a long time, the first dry cargo ships and gas carriers appeared on the horizon like ghosts. It was interesting to watch them through a telephoto lens, as it became clearly visible how they gradually appeared and then disappeared behind the horizon, clearly demonstrating the curvature of the Earth. Somewhere in the distance, the Prirazlomnaya oil platform, its orange torch visible for tens of kilometers, marked its location. Later, we circled Kolguyev Island to the north, a flat tundra area of approximately 3,500–3,700 square kilometers. After some time, we passed the lighthouse at Cape Kanin Nos, at the entrance to the White Sea.

Kola Bay greeted us with unfriendly, stormy, and chilly autumn weather. It is a narrow, deep fjord in the Barents Sea, home to the world’s largest city above the Arctic Circle—the port of Murmansk. Its main feature is its ice-free waters, which gives the bay enormous strategic and economic significance as the base of Russia’s Northern Fleet and a key seaport in the Russian Arctic. Approaching Murmansk, you can see cities such as Polyarny and Severomorsk, docks, berths with nuclear-powered icebreakers, ships, the country’s only aircraft carrier, the Admiral Kuznetsov, as well as countless merchant vessels.

…The shores were golden with autumn colors, the mountain peaks rested against low gray clouds. Alyosha, towering monumentally at the summit, foreshadowed the imminent end of our journey.

We’re back on the mainland, our 19-day adventure to the distant islands has come to an end. The Franz Josef Land archipelago will forever remain in our memories, hearts, and photographs. Perhaps one day fate will take us beyond the 80th parallel. To the high Arctic…

You can order the FJL calendar for 2026 here

Thanks for watching!

My VK

BLOG

Retro-car rally “Victory Circle”

MANPUPUNEUR

Yakutiya

Central Bison Nursery

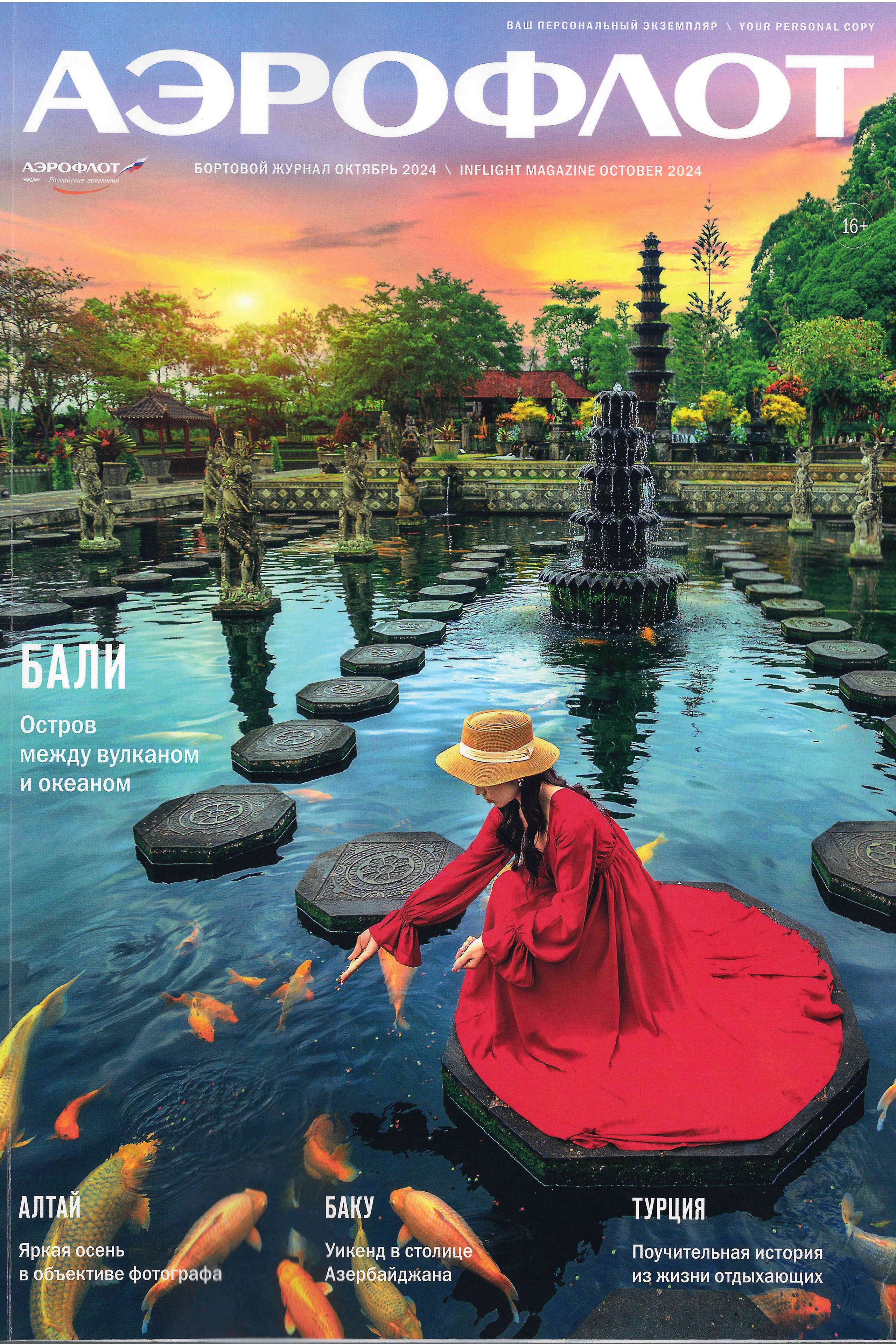

Article in Aeroflot’s in-flight magazine (October 2024)

Aniva Lighthouse

Cycling race “Capital” in Moscow

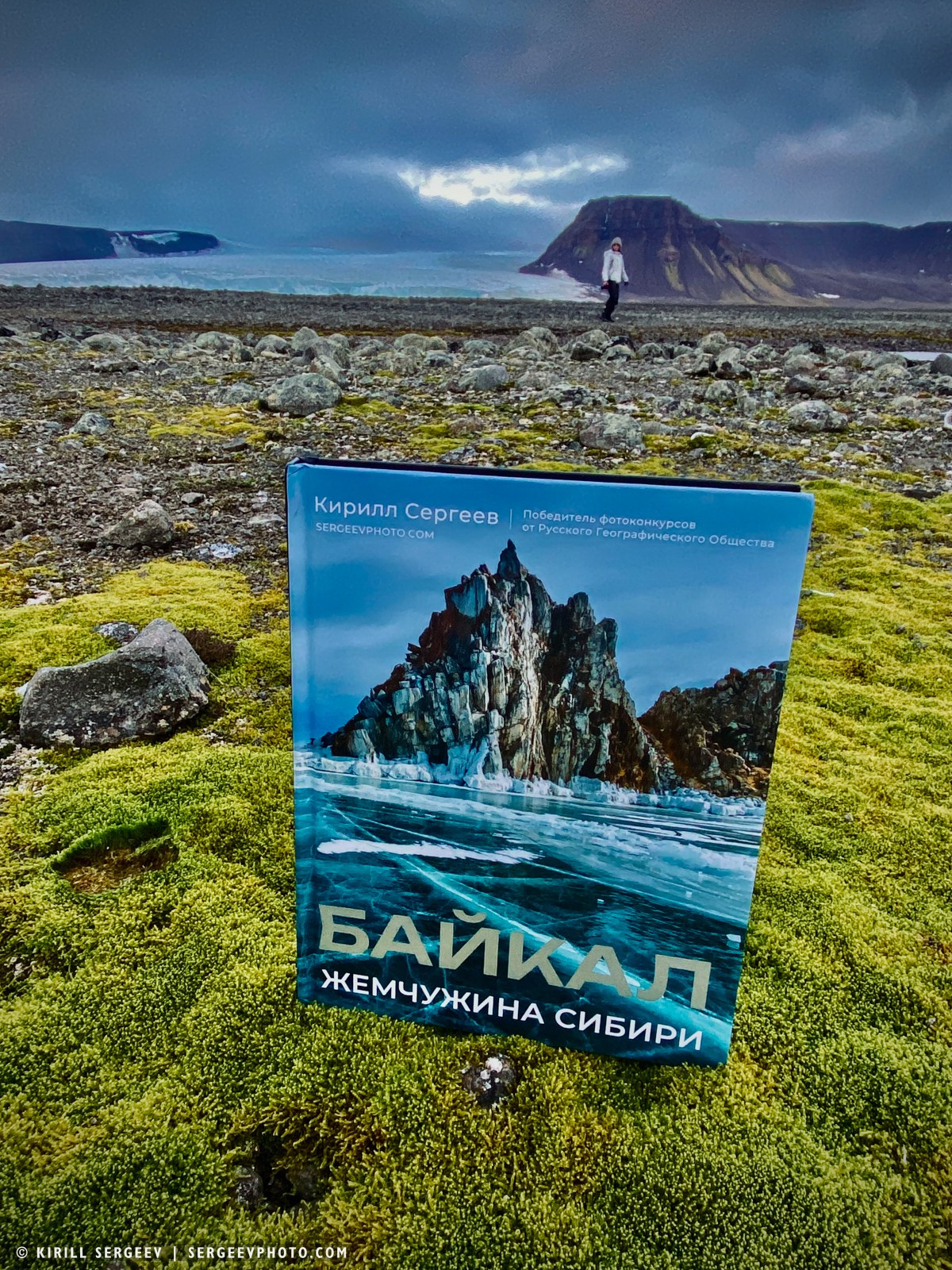

“The most beautiful country”. Victory in a competition from the RGS